Canada can’t afford to fall further behind on this looming global public health threat

The world wasn’t prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless of the steps policymakers could have taken to contain the virus, they could not have foreseen the nature of the virus or prepared for it with treatment or policy before it emerged as a threat. That is not the case with antimicrobial resistance (AMR), one of the World Health Organization’s top 10 global public health threats. But what is AMR and how can our federal government be at the forefront of this next health issue?

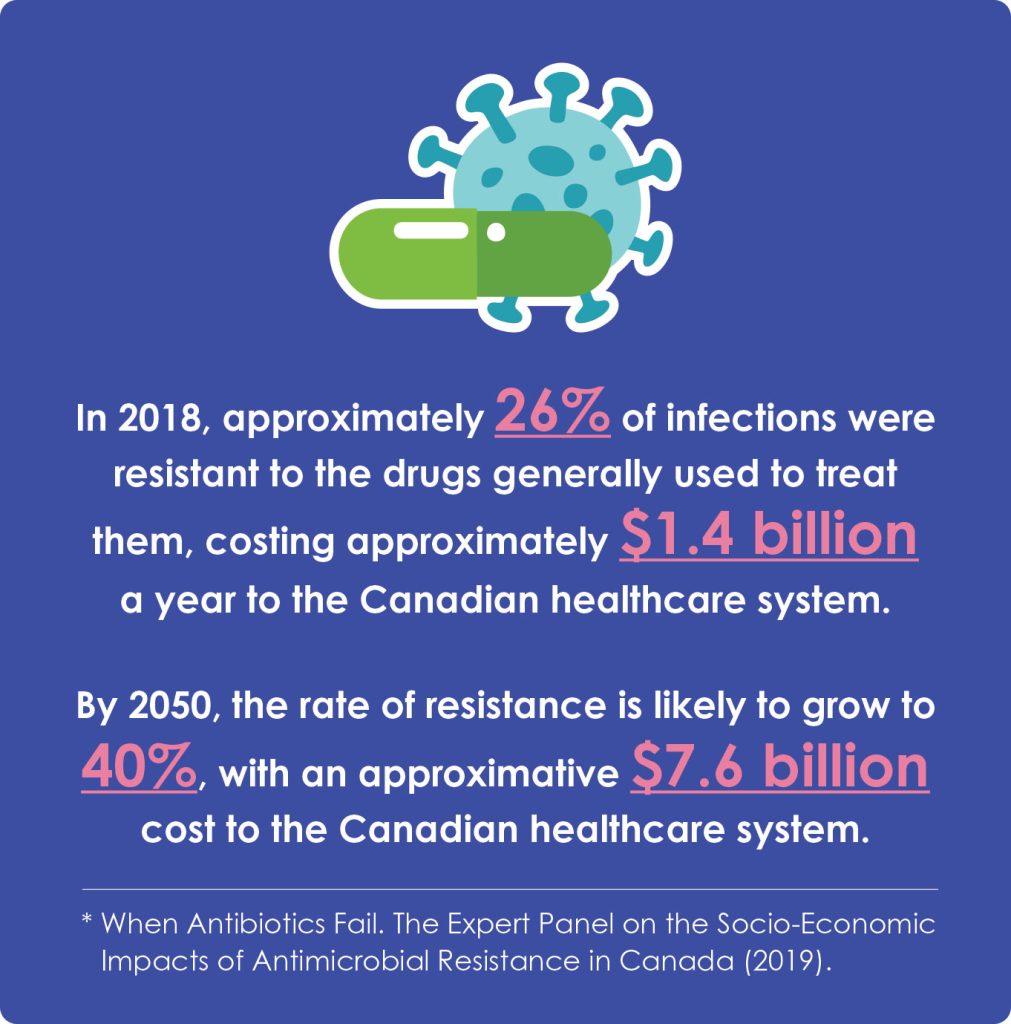

AMR occurs when bacteria develop the ability to resist the antibiotics designed to kill them. Instead of being resolved quickly with antibiotics, disease caused by antibiotic-resistant germs can lead to extended hospital stays, severe illness or even death.

One of the most concerning aspects of AMR is that common infections that were previously relatively simple to cure are now increasingly difficult to treat, like pneumonia or skin and soft tissue infections following a caesarian section. In some cases, health-care practitioners must use more costly and toxic treatments in place of the resisted antibiotics. Experts believe that AMR is being caused, in part, by misuse and overuse of antibiotics in both humans and animals. Disruption of the environment due to extreme weather patterns is also a factor.

Health experts want the public and policymakers to understand the threat posed by AMR, even in an era of COVID fatigue as a recent study in The Lancet showed that in 2019, 1.27 million deaths were directly attributable to AMR, more than malaria and HIV.

Canada has fallen behind

Between 2010 and 2019, 18 novel antibiotics were launched across 14 high-income countries. Only two of these antibiotics are available to Canadian patients. A key barrier is how these medicines are reviewed by Canada’s health technology assessment (HTA) body CADTH, and how they are priced. The current methods do not account for the societal benefit novel antibiotics can offer — notably with respect to mitigating present and future AMR.

Nearly all large pharmaceutical companies have been driven away from antibiotic R&D, and small companies in this space struggle to stay in business due to the significant investment required to develop these drugs, and the challenges with accurately assessing their value for reimbursement.

GSK, a biopharmaceutical company with over 70 years of experience fighting bacterial threats, has been a leader in acting to counter AMR, with a strong track record in developing cooperative solutions to help Canada lead the charge in the global fight against AMR. Ranya El-Masri, GSK Canada’s vice-president and head of government affairs and market access, believes now is the time for industry and governments to act decisively.

“COVID-19 has taught governments and innovators two critical lessons when it comes to tackling AMR and infectious disease across the board,” says El-Masri. “First, time is not on our side. For many, antibiotics may currently be effective, but we cannot afford to wait while resistance to antimicrobials continues to accelerate at pace. Second, we need to draw on the full gamut of our scientific firepower including antibiotics, vaccines, and other potential complementary interventions, like monoclonal antibodies for the benefit of patients and our healthcare systems.”

She elaborates: “Building on our long history in antibiotic development, GSK has a number of projects in our pipeline targeting priority pathogens deemed ‘critical’ and ‘urgent’ by WHO and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This includes an innovative antibiotic. And, over the past two years, we have expanded vaccine research programs that could help counter AMR. The 2021 AMR Benchmark recognized GSK as having the largest R&D pipeline among the big R&D-based companies.”

Preparation will be on every mind at the upcoming G7 Health Ministers’ meeting in Nagasaki, Japan this May. The emerging public health issue that is AMR will be high on the agenda as it is a global threat that will be indifferent to country borders.

El-Masri’s message to policymakers is clear: “It is essential this issue be addressed with a degree of urgency in 2023, commensurate with the threat it poses. With the right collaborations and frameworks in place to proactively and sustainably fund new technologies, we can get ahead of antimicrobial resistance together.”

Recently, the federal government has made some commitments toward addressing the issues of AMR. In 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau mandated Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos to “work with partners to take increased and expedited action to monitor, prevent and mitigate the serious and growing threat of antimicrobial resistance and preserve the effectiveness of the antimicrobials Canadians rely upon every day.”

Yet, Canada has not followed the AMR lead of other countries such as Great Britain, Sweden and Germany which have designed incentives — along with regulatory agility and accelerated timelines for reviews — that have fostered important diversity in the antibiotics pipeline. All while ensuring good stewardship and cost sustainability. These actions resulted in rapid and impactful changes facilitating access to novel antibiotics for their citizens to help slow the progression of AMR.

May’s G7 Health Ministers’ Meeting is a reminder that Canada is part of a global effort to eradicate the threat of AMR. Many in the health-care community believe now is the time to unleash made-in-Canada innovations and demonstrate leadership. The best path forward has policymakers and industry taking those steps together.

Sponsored Content On Behalf of GSK.